Museum of the Filipino People: The National Museum’s other museum in Manila

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. When you buy through links on my site, I may earn a small commission. Thank you for your support.

Museum of the Filipino People building facade

On June 30, 2016, while the Philippines inaugurated a new president and vice-president, Motito and I were admiring the vast collection of cultural and archaeological artefacts at the Museum of the Filipino People. It was the final day to take advantage of the free admission that started in May in celebration of the National Heritage Month and was graciously extended to June. Later in the evening, the National Museum would announce that beginning July 1, admission to all its museums throughout the country will be permanently free of charge.

My social media feeds were abruptly filled with posts from folks expressing gratitude for the free admission and making plans to visit the National Museum at the soonest. I wonder if they’re mostly referring only to the National Art Gallery, the component museum of the National Museum that sees the highest visitor traffic. My son and I visited the National Art Gallery on a Sunday in May and had to wait in a queue to get in. In contrast, the Museum of the Filipino people see fewer museum-goers, except when it’s a designated stop in a school field trip or an art appreciation tour.

The less popular Museum of the Filipino People is a stone’s throw (almost literally, if one could throw that far) from the National Art Gallery, in the heritage-rich part of Manila where you’ll also find the Rizal Park, Intramuros, Fort Santiago, and the Manila Cathedral. On the day of our visit, we saw a group of college students on an educational trip and a smattering of high schoolers from the nearby schools. How fortunate these kids are to be going to these schools, with so much culture and history in the neighborhood, I thought, as I signed our names in the visitors’ log and checked my bag.

Ifugao house at the Museum of the Filipino People

Occupying the former Department of Finance building designed by architect Antonio Toledo, the Museum of the Filipino People comprises four levels accessible to visitors. In the museum courtyard stands an authentic Ifugao house, particularly an Ayangan house from Mayaoyao, Ifugao. The one-room house has three levels: a ground level, a second level that serves as the living area, and the third level that is used as a granary. Since no nails or bolts are used, an Ifugao house can easily be disassembled, moved to a new site, and re-assembled.

Taxidermy visible storage at the Museum of the Filipino People

Level 1 of the museum has a visible storage of taxidermied animals from the museum’s zoological reference collection. The stuffed and preserved animals are kept in a restricted area, but can be viewed through the transparent glass wall. Among the animals “represented” in the collection are a Philippine hornbill, a crocodile, a lemur, butterflies, and what looked like a gecko (sorry, I can’t remember).

National Museum Library

Also on Level 1 is the National Museum Library, which is a soothingly lit, quiet room with an adequate collection of books and periodicals about Philippine history and culture. Motito busied himself studying the globe, while I sat down and browsed the day’s papers. We could’ve stayed there all day, but we had a museum to explore.

Garing: The Philippines at the Crossroads of Ivory Trade

We went up to Level 2 and proceeded to Garing: The Philippines at the Crossroads of Ivory Trade. This exhibit explores the early roots of ivory trade in the country while raising awareness about the fight against elephant poaching and the illegal trafficking in ivory. I recalled a 2012 National Geographic article about the Philippine connection in illegal ivory trade. Tons of illegal ivory were seized by customs in Manila in 2005 and 2009; Taiwanese customs seized tons bound for Manila in 2006. The elephant tasks are carved into religious figures and amulets in the Philippines and sold locally or exported to other countries. Garing is the Filipino word for ivory. Displayed in the exhibit are elephant tusks recovered from the Lena Shoal wreck in Busuanga, Palawan, in 1997, as well as objects carved out of ivory. The exhibit also shows natural and synthetic substitutes for ivory.

The San Diego: A Homecoming Exhibit

Next we explored “The San Diego: A Homecoming Exhibit,” which features artefacts recovered from the wreckage of the Spanish battleship that was sunk by the Dutch ship Mauritius on December 14, 1600. On display are ceramics, potteries, coins, jewelry, armaments and other fascinating objects. Full-sized cannons and cannonballs, helmets, an ancient navigational instrument, and the ship’s log of the fateful voyage are also showcased in the gallery. The San Diego’s massive anchor, heavily encrusted in sediment, was a real eye-catcher. Also on exhibit are paintings that explore the roots of the Manila galleon trade.

Linnaeus and the Linnaeans, Museum of the Filipino People

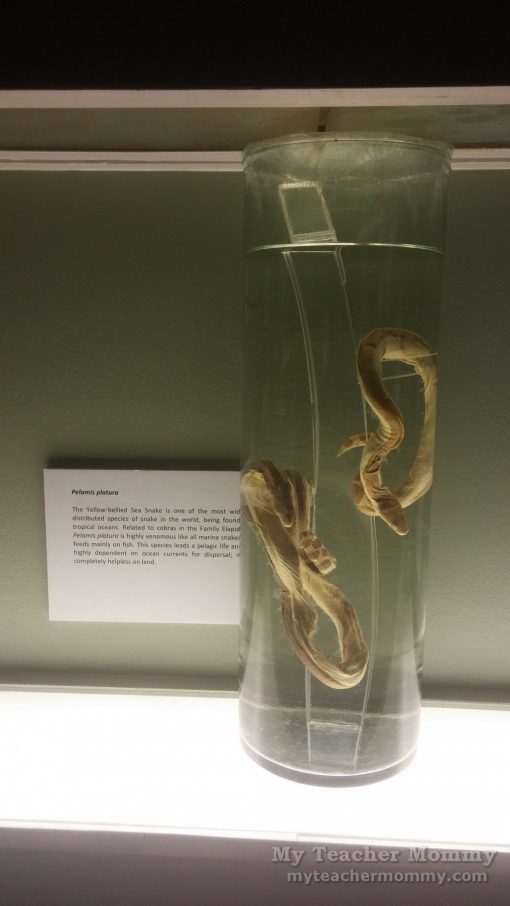

Next we walked into a small gallery dedicated Swedish botanist, physician and zoologist Carl Linnaeus, considered the “father of modern taxonomy.” The Linnaean taxonomy is showcased using several taxidermied animals found in the Philippines. Inside glass encasements are a Philippine flying lemur, a tarsier, a Nicobar pigeon, a blue-naped parrot, a sleepy sponge crab, a flying lizard, a pair of yellow-bellied sea snakes, tailed green jay butterflies, migratory locusts, sea shells and cones. The gallery looks to be a work in progress, as the plant displays have been temporarily removed for safekeeping.

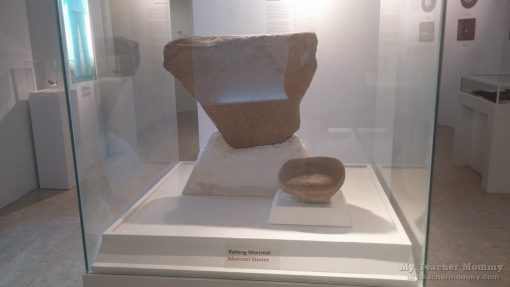

Kaban ng Lahi (Archaeological Treasures)

Up the stairs we enter the first of three exhibits on Level 3, “Kaban ng Lahi: Archaeological Treasures.” This exhibit depicts burial practices of early Filipinos in southern Philippines and other parts of the country. One practice involved a secondary burial, wherein the deceased’s bones were treated and re-buried after the body had decomposed. The bones were placed in earthenware jars sculpted to represent humans. Various burial urns are displayed, with the sculpted human “heads” showing different facial expressions. There is a diorama illustrating how the burial jars appeared when they were discovered in Ayub cave in Maitum, Saranggani in 1991.

Lumad Mindano and Faith, Tradition and Place: Bangsamoro Art from the National Ethnographic Collection

Two ethnographic exhibitions focus on the Bangsamoro and the Lumads. “Faith, Tradition and Place: Bangsamoro Art” aims to enrich and deepen our awareness of the traditions and spirituality of our Muslim brothers and sisters. On display are musical instruments like the kutiyapi, gangsa, kulintang, tambur and zither, as well as household and farming implements. There are weapons such as kris, barong, kampilan, pira, gunong, and amulets and talismans believed to provide protection from harm. Of particular eminence is the Quran of Bayang, which belonged to the Sultan of Bayang in Lanao del Sur and was copied by Saidna, one of the earliest hajji. “Lumad Mindanao” offers insights on the Lumads’ ways of subsistence, belief systems, decorative arts, personal adornments, household and community life. On exhibit are household and cooking implements, tools for farming and hunting, baskets of various shapes and sizes, made of bamboo, rattan and pandan, and personal adornments like glass beads, shells, vines, seeds, locally made brass hats, necklaces and pendants, finger and toe rings. Wood sculptures of birds symbolize the significance of the animal in the ecology and lore of the Lumads. Woven textiles and cloth showcase the unique craftsmanship of the Bangsamoro and Lumad people.

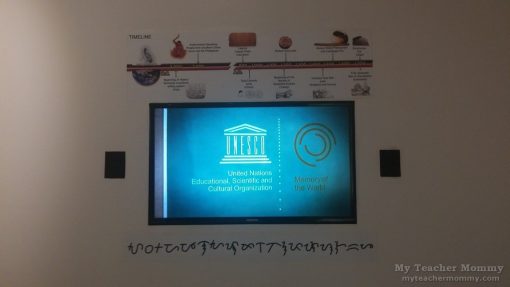

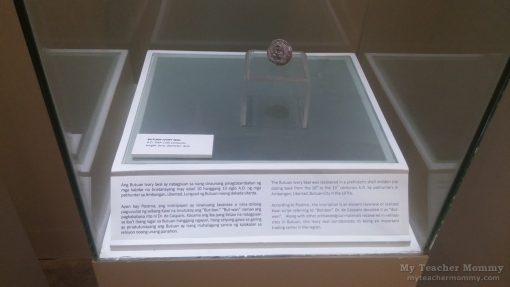

Baybayin Exhibit, Museum of the Filipino People

Two more galleries awaited us on Level 4. “Baybayin: Ancient Scripts of the Philippines” Level 4 showcases the ancient Philippine script that was first noted in the 16th century. Like many of the writing systems in southeast Asia, Baybayin may have descended from ancient scripts used in India around 2,000 years ago. Notable artefacts in the exhibit include the Laguna Copperplate inscription and the Butuan Ivory Seal, both of which are written in Kawi script, believed to be a precedent of Baybayin. There’s a table with a Baybayin chart, blank sheets of paper, and pens where visitors can try their hand at writing in Baybayin.

Hibla ng Lahing Filipino: The Artistry of Philippine Textiles

“Hibla ng Lahing Filipino: The Artistry of Philippine Textiles” pays homage to the Philippines’ centuries-old weaving traditions by shining the spotlight on our ethnic weaves and fabrics. Colorful, unique cloth weaves reflect the artistry and craftsmanship of indigenous communities in the country where weaving is a deeply-rooted tradition. Featured in the exhibit are heritage textiles and clothing, traditional weaving looms like the piña foot loom and abaca backstrap loom, as well as historic photographs of Filipinos in traditional garb and modern images of indigenous Filipinos in their native wear.

The museum visit was two hours well-spent for me and my son. The exhibits provide a fascinating walk through Filipinos’ diverse cultural heritage and give valuable insights into how history continues to shape our present and future. I look forward to visiting with Motito again when a new exhibit opens.

The Museum of the Filipino People is located on Finance Road, between P. Burgos and Taft Avenue, Manila. It is open from Tuesday to Sunday, 10AM-5PM. Admission is free of charge. Click here for directions to the museum. for