Money matters, especially during a zombie apocalypse: Teaching money in homeschool math

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. When you buy through links on my site, I may earn a small commission. Thank you for your support.

A horde of brain-devouring zombies is barreling through the now-desolate city. These are not the slow zombies of George A. Romero film lore. We’re talking sprinting, galloping, going from zero to 60 type of undead. Panic-stricken residents have flown the coop, but you, along with a small but determined pack of undaunted souls, have elected to hold down the fort and keep the zombies from advancing into the neighboring cities. But first, you must arm yourself to the teeth. And in this town there’s only one guy who knows his shotguns, crossbows, and machetes. His name is Mad Motito, and his ammo store is offering a half-price special on lawnmowers for a limited time. “Limited time,” you chuckle. The only ones who’re running out of time here are those blasted brain-eaters. Pure adrenaline courses through your veins as you bust Mad Motito’s doors open. The ammo dealer looks up from polishing his rifle, then cracks a toothy smile. “Well, well, well. Lookie what we got here!,” he says, then quickly chides “I was beginnin’ to think you’d sit this one out.” Mad Motito adjusts his baseball cap as he regards you with steely eyes. “Now how may I help you this fine blood-soaked mornin’?”

Thus went the plot that Motito had woven for our homeschool math role-play about money. This was my first attempt at teaching money to him formally, and I was pretty excited about our set-up. I must confess that I don’t give Motito ample opportunity to handle coins and notes on his own. I blame that on my (sometimes) irrational fear of disease-causing bacteria that might lurk in dirty, tattered notes or grimy coins. I also worry about him losing cash due to carelessness. I’ve lightened up a bit and occasionally send Motito on errands to the general store nearby or have him fish out the exact jeepney fare from my purse.

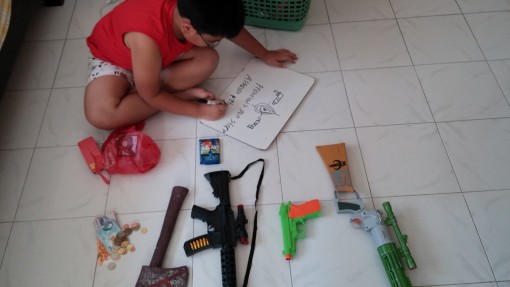

There are lots of creative ways to teach children about money, depending on their grade level. Preschoolers can sort and stack coins or bills, or create colorful impressions of coins by putting a coin under a paper and rubbing a colored pencil or crayon over the coin. Students in early primary can play grocery or restaurant, or a round of Monopoly. When told that he could pretend to run any store he wanted for our math activity, Motito readily put up an ammunition store, where he said I could purchase weapons to prepare for an impending zombie outbreak. I suggested perhaps he could sell seeds instead, so I might grow plants like the ones on “Plants vs. Zombies.” He rolled his eyes and said “You can’t use plants to blow up zombies in real-life, Mommy. Duh!” He’s right.

Some experts believe that for primary schoolers, using real coins and notes when teaching money is preferable to using paper money. It is important to familiarize children with how real money looks and feels in their hands. This can be helpful when teaching them how to discriminate between real and counterfeit or fake money. Sooner than later these children will be handling the real thing when buying something from the school cafeteria or bookstore. Knowing what combination of coins and notes make up a certain amount is useful when deciding if they have enough to make a purchase or if they were given the correct change. Role play that involves buying or paying for something is an effective way to show that money has value and can be exchanged for something of perceived equal value.

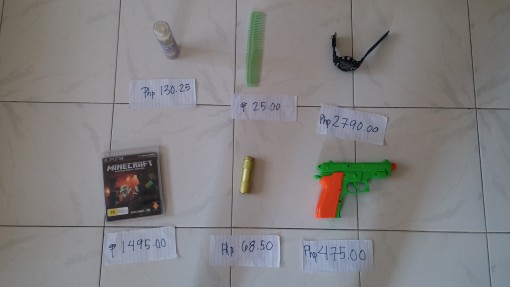

For our homeschool math activity, Motito and I took turns as buyer and seller. Our first role play involved general items found around the house, like a pair of scissors, a baseball cap, etc., because I wanted a more realistic scenario before playing out a fantastic one (the zombie outbreak premise). Initially he played the buyer, and he had to pay me the exact amount of the item he wanted. In addition, I made him count out the same amount in different coin and note combinations. When it was my turn to buy, I did not hand him the exact payment, so he had to give me the correct change. Aside from making him calculate change using the standard subtraction algorithm, I also taught him how to make change using the “counting up” strategy.

If you’ve ever shopped at a wet-and-dry market or your friendly neighborhood sari-sari store, chances are you have seen the “counting up” method of giving change in action. In this strategy, the person giving change will start counting from the purchase price up to the amount given as payment. Let’s say the amount due is 136.75 pesos and the buyer hands you a 500 peso bill. You start by counting out to the next higher denominaton. In this case, you count out a 25 centavo coin to get from 136.75 to 137.00. Next, you count out one-peso coins to get to 140 (that’s 137…138…139….140, which works out to three pesos). Afterwards, you count up from 140 to 200 using either three 20-peso bills (140…160…180…200) or one 50-peso bill and a 10-peso coin (140…190…200). Finally, you count up from 200 to 500 by using three 100-peso bills (200…300…400…500). When you are done, you will have counted out 0.25 + 3.00 + 60.00 + 300 = 363.25 pesos. Counting up is a very practical and accurate way of making change. From a teaching standpoint, counting up reinforces the concept of addition as the inverse of subtraction.

We did the activity for three days, alternating as buyer and seller and using other items we could grab around the house. Motito can now easily recognize coins and notes by sight (without having to read the value stated on them). So when a zombie apocalypse does happen, I now know whom to send running to the hardware store for some hacksaws and sledgehammers. 🙂