National Museum of the Philippines: The National Art Gallery

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. When you buy through links on my site, I may earn a small commission. Thank you for your support.

Housed in the old Legislative Building along P. Burgos Drive in Ermita, Manila, the National Museum of the Philippines stands proudly among the historic sites in this part of the 445-year-old city. With Intramuros, Fort Santiago, the San Agustin Church, and Rizal Park just around the corner, the National Museum is an ideal place to start if you’re seeking to know more about Filipino heritage, culture, and identity. The National Museum operates the National Art Gallery, the Museum of the Filipino People, the Planetarium, and regional museums across country. Starting July 1, 2016, admission to the National Museum and its branch museums is free of charge.

We went to the National Art Gallery on a Sunday and saw a long queue of weekenders and tourists waiting to get inside its hallowed halls. The doorkeepers were letting about 30 people in at a time. We stepped into climate-controlled comfort after a 20-minute wait in the sweltering outdoors. After queuing up to register and check my bag, we ambled into the main hall on Level 2 (House Floor), which is where visitors generally start. National Artist Guillermo Tolentino’s Untitled (Diwata), a sculpture of a winged fairy in reinforced concrete, welcomes visitors to the hall.

Exhibits on the House Floor cover Philippine Art from 17th to 20th centuries. The first thing that will catch your eye is the jaw-dropping spectacle of Juan Luna’s Spoliarium. Luna’s world-renowed masterpiece paints a gruesome aftermath of Roman gladiator matches, taking us to the dank basement of the colosseum where wounded and dying gladiators are dragged and disposed of unceremoniously, while spectators either grieve or wait to get their hands on the dead’s possessions. A gold medal winner in the 1884 Madrid Exposition, the oil-on-canvas measures an imposing 4.22 m x 7.68m, just the perfect size to have one’s selfie taken in the foreground, as many museum-goers apparently thought.

Across from Spoliarium in the same hall is Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo’s El Asesinato del Gobernador Bustamante (The Assassination of Governor Bustamante). The 19th-century oil-on-canvas dramatizes the assassination of the Governor General to the Philippines Fernando Bustamante by a mob of vengeful friars. Hidalgo bagged the silver medal in the1884 Madrid Exposition for his painting Virgenes Cristianas Expuestas al Populacho (Christian virgins Exposed to the Populace). Two Filipino masters taking plum prizes in an international art exposition. That’s like having Filipina beauties crowned as Miss Universe and Miss World in the same year.

Hundreds of artworks and artifacts are displayed in approximately 25 exhibitions in the entire museum. Sculptures, paintings, drawings, and prints gracefully line the corridors and doorways. On Level II you’ll find Christian-themed art from the 17th to the 19th centuries, including wooden carvings of saints and reliefs and paintings of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ. Many of these artworks were made by unknown artists, including 14 works of oil on wood panel depicting the Via Crucis or Stations of the Cross. Be awed by an antique retablo, or altar piece, from the Church of San Nicolas de Tolentino in Dimiao, Bohol, which is considered a national cultural treasure. Also on the House Floor is a gallery that celebrates the life and heroism of Dr. Jose Rizal. Here you’ll find portrait busts and paintings of Rizal by distinguished Filipino artists from the early to mid-20th century.

Along the hallway are hung art prints of Philippine flora from the archives of the Royal Botanical Garden in Madrid. Commissioned by Spanish pharmacologist and botanist Juan Jose de Cuellar, the drawings show Philippine plants that he had collected from his field work in Luzon in the mid-1700s. Motito and I liked this gallery particularly, delighting in learning the scientific names of our native plants and their common uses.

Also catching my fancy was the gallery devoted to Philippine portraiture from mid- to late 19th century. Masterful strokes capture the expressions and poses of mothers and daughters, fathers and sons, luminaries, dreamers, and peasants. Anonymous many of the subjects may be, they are immortalized in extraordinary portraits for generations to see.

A gallery devoted to classical art from the 20th century features works by National Artist Fernando Amorsolo, his cousin and mentor Fabian de la Rosa, Ireneo Miranda, Cesar Buenaventura, Zosimo F. Dimaano, and other notable artists. The idyllic rural landscapes and countryside scenes depict peaceful times before World War II. Looking at paintings of bahay-kubo, rice fields, waterfalls, and fishing boats, I was reminded of the rustic-themed oil paintings that hung in many modest homes I’d been to in the 1980s.

The life and works National Artist for Sculpture Guillermo E. Tolentino are honored in the Security Bank Hall. The iconic Filipino artist has left the nation a lasting legacy with the “Oblation” on the UP campus, the Bonifacio Monument in Caloocan City, as well as the design of the medal for the Ramon Magsaysay Award and the seal of the Republic of the Philippines. Portrait busts of Philippine presidents, bas-reliefs, sculptures, drawings and lithographs are featured in the Guillermo exhibition, along with valuable memorabilia like diplomas, certificates, and plaques.

On Level III (Senate Floor), you’ll come upon the old Senate Session Hall, which has been restored to its pre-war grandeur through a P20M project funded mainly by PAGCOR. Concrete balustrades have been replaced with faithful reproductions, while spot corrections revitalized the hall’s geometric fretwork and sculpted garland. The overhead statues, made by sculptor Isabelo Tampinco, represent great lawmakers and moralists of history, including Kalantiaw, Apolinario Mabini, Augustus, Solon, Pope Leo XIII, and Woodrow Wilson.

At the restored Senate Hall, we happened upon the exhibition “A Vision for the Sensual City,” by French architect Jacques Ferrier. The exhibit showcases scale models of some of Ferrier’s famous work, such as the French Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo.

The best of Philippine Modernist art from the 1920s to the 1970s, spearheaded by National Artist Victorio C. Edades, takes center stage in an exhibition that also features works by Anita Magsaysay-Ho, Manuel Rodriguez Sr., Juvenal Sanso and Galo Ocampo, and sculptures by Jose Alcantara and National Artist Napoleon Abueva. Sanso’s The Man with a Hoe took me back to my high school days when Edwin Markham’s poem on the plight of the working class was the declamation piece du jour. (It bears reminding that Markham’s poem was inspired by Jean-François Millet’s painting L’homme à la houe).

Also on Level III are separate exhibitions showcasing the works of National Artist Vicente Manansala and Emilio “Abe” Aguilar Cruz. Manansala, whose most popular work is the Madonna of the Slums, is widely considered as the pioneer of Cubism in Philippine art. A prolific painter, Cruz, who was also a writer and epicure, is believed to have produced as many as 5,000 pieces. He co-founded the Dimasalang Group of artists with Sofronio Ylanan Mendoza in 1968.

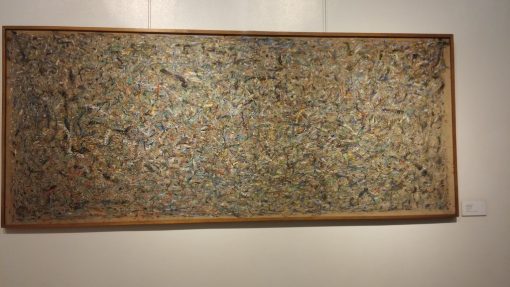

The South Hallway Gallery features selected works representing Philippine abstraction from the 1960s to the 1980s. Artists whose creations are showcased in this gallery include Dave Aquino, Mike Aquino, Rock Drilon, Romulo Olazo, and Cenon Rivera. Another hallway gallery displays modern and contemporary art by Pacita Abad, Manuel Baldemor, Norman Belleza, Jaime de Guzman, and others.

More than two hours had passed by the time we were done viewing the last gallery, yet I had the feeling we hadn’t covered the entire museum. I blame my directional dyslexia for my poor sense of direction and low spatial awareness. It was only when I was reading more about the National Museum later that day that I learned we’d missed The Progress of Medicine in the Philippines, by National Artist Carlos “Botong” V. Francisco, the drawings of Fernando Amorsolo and the Homage to Dr. Jose Rizal (despite my mentioning it here, I never actually saw it). I realize this oversight that can be corrected with another visit in the future. With admission to the National Museum of the Philippines now free of charge, I’ve no excuse not to return.